|

|

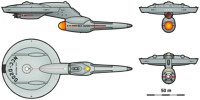

Avenger- and Predator-Class Destroyers

![]() Diagrams

Diagrams![]()

Avenger |

Predator |

Avenger and Predator |

Avenger deck plans created by Allen Rolfes (see notes) |

Predator deck plans created by Allen Rolfes (see notes) |

Destroyers and Sahara-class tender |

Common bluescale plans, part 1 created by Allen Rolfes (see legend) |

Common bluescale plans, part 2 created by Allen Rolfes (see legend) |

Common bluescale plans, part 3 created by Allen Rolfes (see legend) |

Common bluescale plans, part 4 created by Allen Rolfes (see legend) |

![]() Scenes

Scenes

![]()

Avenger created by Jan Seebald |

Avenger created by Jan Seebald |

Avenger firing created by Jan Seebald |

Predator created by Jan Seebald |

Avengers, Predators & Constitution created by Jan Seebald |

Avenger created by Skyhawk223 |

Avenger created by Skyhawk223 |

Avenger and Jupiter created by Skyhawk223 |

Avenger and Predator render by kobosh, mesh by Terradyhne |

Avenger and Predator render by kobosh, mesh by Terradyhne |

Avenger and Predator render by kobosh, mesh by Terradyhne |

D6 surrounded by Predators created by Thomas Pemberton |

![]() History

History![]()

The Avenger and Predator classes of destroyers were built in large numbers in the 2250s for the Federation's cold war against the Klingon Empire. However, by performing their intended roles extremely well, they were also instrumental in bringing about the Four Days' War of 2267.

The Treaty of Korvat

The late 2240s saw great changes in the Federation's relations with the Klingon Empire. The Klingons' attempted invasion of the Archanis sector in 2244 had ended in failure at the Battles of Donatu V and Tassem-Loki III and indicated to all but the most irrational Klingons that large-scale conquest of Federation territory was unlikely, at least for the foreseeable future. In 2247 Klingon Chancellor K'tok, who had seized power in the political turmoil following this humiliating defeat, prohibited any further attempts to expand into Federation-held territory. As expected, K'tok's edict was not welcomed by all Klingons. The next year, two rogue Klingon Great Houses, Temosh and Maach, made deep attacks into Federation-controlled space at Delta Ginax and Middlefinger in an attempt to spark a wider war. Starfleet contained and repelled these attacks, but only with significant loss of life. To help ensure that any further attacks would be criminal acts without the sanction of the Empire, in 2249 the Klingons and the Federation negotiated (with the help of mediators from the then neutral worlds of Ramatis III and Trillius Prime) and signed the Treaty of Korvat, which normalized relations and established the powers' respective borders and an intervening Treaty Buffer Zone (TBZ) whose final disposition would be determined with subsequent negotiations. The treaty also enabled the Klingons to shift their defenses away from the Federation border to deal with their other long-time rival, the Romulan Star Empire.

The Federation Resource-Denial Campaign

The Klingons' decisions to agree to negotiations, then sign the Treaty of Korvat, puzzled the Federation. Why would an empire that had launched countless attacks against the Federation suddenly forswear all territorial expansion in the Alpha Quadrant? Were the Klingon Empire's diplomatic overtures a welcome first step toward its becoming a member in good standing of the wider galactic community? Or was the treaty all part of an elaborate stratagem to weaken Federation defenses? Although many Federation citizens had a sincere desire for peaceful relations with the Klingons, the more prevalent view, held by most Starfleet analysts, was that the Treaty of Korvat marked only a moratorium on Klingon aggression, which would resume once the Klingons had recovered from their recent setbacks. When this recovery would be complete was unknown, as the Klingon Empire had a much smaller, homogenous population, a less diversified industrial base, and a less-dynamic scientific and commercial culture.

However, many within the Federation and within Starfleet saw signs of weakness and growing desperation in the new face of the Klingon Empire. The Federation knew that an important reason for the Klingons' apparently insatiable hunger for expansion was a severe shortage of mineral resources. Unlike the Federation, which was blessed with numerous planetary treasure houses, such as Argus X, Delta Ginax, Janus VI, and Mirabella G, the Klingon Empire was cursed with many star systems comprising mostly gas giants. To secure mineral resources they deemed necessary for their survival, the Klingons had traditionally conquered weaker powers, exterminated or enslaved their people, and strip-mined their planets. As the Klingons had been an aggressive, space-faring race for more than a millennium, they had to range further and further from their homeworlds to obtain resources. After their attempts to expand into the Federation-dominated Alpha Quadrant had been thwarted, the Klingons were less able to secure these mineral resources through conquest and were now attempting to secure them through trade and diplomacy.

Although the resource-poor Klingons often claimed they "conquered to survive," the Federation instead believed that the Klingons "survived to conquer" and would continue to make war on their neighbors if able to do so. Indeed, even after signing the Treaty of Korvat, the Klingons continued their traditional predations along their resource-poor antispinward frontier, far from Qo'noS and Federation-controlled space. Therefore, Federation strategists surmised that control of resources might be the key to preventing future Klingon expansion attempts in the Alpha Quadrant. Some even saw a historic opportunity to solve the "Klingon problem" once and for all, either through decisive military defeat of a weakened Klingon Empire or through a less drastic, but still radical, "domestication" of the Klingons by providing them with a carefully controlled, behavior-linked supply of mineral resources. However, for now the Federation would try to severely limit the supply of resources to the Empire to prevent Klingon aggression. Of course, such a strategy might backfire by making the Klingons even more desperate for resources and expansion, thereby sparking full-scale war. However, the Federation reckoned that a weakened, though desperate, Klingon Empire would be more easily dealt with than would an ambitious, well-nourished Klingon Empire.

Therefore, in 2249 the Federation devised a two-stage plan to deny resources to the Klingon Empire. In the first stage, to be implemented immediately, the Federation would attempt to conclude limiting or exclusive trade and defense agreements with neutral powers and claim control over large areas of uncolonized space. In the second, more aggressive stage to be implemented sometime in the future, the Federation hoped to destabilize Klingon mining operations, interrupt resource shipments to and from colony worlds, sabotage Klingon relations with other powers, and generally frustrate free movements of Klingon ships inside and outside the Empire.

Klingon Diplomatic and Trade Problems

Although the Federation planned to undermine Klingon diplomatic efforts in the Alpha Quadrant, the Klingons were poor diplomats, even without interference. Starting in 2247, the Klingon Empire sent its ambassadors to the Federation's capital on Earth, to many Federation member worlds, and to important neutral powers and, in turn, welcomed ambassadors to Qo'noS. The Klingons had always been skilled in the application of force and intimidation but were still inexperienced in the gentler art of diplomatic persuasion. Furthermore, the Klingons viewed diplomacy with great suspicion, since negotiations in the Empire had traditionally served as a mask for one's real intentions. Accordingly, Klingons believed that telling the truth in negotiations was for the foolish or feeble-minded. In addition, members of traditionally strong warrior Houses were unwilling to serve as diplomats, as they believed verbal persuasion was a recourse only for those too weak to fight. Therefore, Klingon diplomatic efforts were often undertaken in bad faith or were unsupported or even sabotaged by Klingon military actions. In contrast, the Federation owed its very existence to finely honed diplomatic skills and delicate negotiations. Exceedingly patient Federation diplomats deftly offered flattery, developmental assistance, advanced technology, and military protection to new friends and allies, often bending, if not breaking, the provisions of the Prime Directive. These efforts allowed the Federation to secure many mining agreements and development contracts, often exclusive and at the expense of the Klingons. The Klingons, on the other hand, had traditionally ruled the subject worlds of their Empire with terror and utter brutality. Accordingly, in exchange for mining rights or basing privileges on neutral worlds in free space, the Klingons initially couldn't conceive of offering much more than a promise of continued survival or, at best, help in crushing one's enemies.

As bad as the Klingons were at diplomacy, they were even worse at trade. The primary reason was that commerce was traditionally viewed by the ruling warrior class as a contemptuous, barely necessary evil. As a result, the Klingon economic system was extremely primitive and inefficient, relying on commands from central authorities at every step of production. What little trade occurred was primarily through barter of raw materials, finished goods, military service, fealty, or territory. There was no universally accepted currency, no banking system, and no stock markets. Labor was often done by slaves (Klingon and alien) or by persons bound by long-term, often hereditary contracts of servitude. Therefore, the Klingons were ill-equipped for commercial relations with other races. Unfamiliar with the values of commodities and services on the open galactic market, the Klingons were often cheated by unscrupulous merchants and middlemen. Although the Klingons coveted raw materials, they had no hard currency to pay for them. Instead, payment often required a complex series of barters, each of which increased the final cost to the Klingons. The Klingons also had very little in the way of finished goods that advanced races wanted. Although Klingon artisans did produce highly prized bladed weapons, armor, jewelry, and art objects, both output and demand were too low to support the import of raw materials in the desired industrial quantities. The same problem confronted offers of Klingon culinary delicacies and cultural items. Advanced Klingon weapons systems, such as warships, were desired by some races, but exporting them would have defeated the entire purpose of Klingon trade. However, the Klingons could export primitive or obsolete weaponry and machinery to less-advanced races or could export military intervention to less-powerful races wishing to overcome enemies. Although the Klingons learned the hard way that the buyer must always beware, their experiences confirmed their conviction that peaceful methods were unlikely to meet their resource needs.

A New Federation Defense Policy

Although the Federation and the Klingon Empire were no longer staring each other down across a heavily militarized border, their competition had migrated into another arena. The new battleground of the mid-23rd century was in uncolonized areas of space and in the hearts and minds of neutral powers. Both sides now attempted to expand their respective spheres of influence to create an interlocking interstellar web of commerce, diplomacy, and defense. They also attempted to be the first to exploit the resources of uncontrolled star systems and thereby deny their rival the benefits of the same. The heavy cruisers of the Pyotr Velikiy and Constitution classes, introduced in 2241 and 2245, boldly pushed far beyond the existing borders of the Federation, establishing an extremely strong Federation presence across vast areas of space, including areas the Klingons had considered under their control. The strength of the new classes allowed the Federation to make contact with scores of civilizations, who more often then not became trading partners, allies, or even new members of the Federation.

The introduction of the Constitution and Pyotr Velikiy classes during the 2240s also lead to a reassessment of Starfleet defense policies. The Command Directive of 2221 had called for peripherally based light cruisers, such as those of the Paris and Kestrel classes, to be the front line of Federation defense. These light cruisers were expected to immediately engage any attackers and remain in combat until heavy cruisers arrived from their reserve stations light-years behind the border. Although this reactive defense policy had successfully repelled all attempted invasions of Federation space, it had done so only at great cost in ships and lives, both civilian and Starfleet. Because single light cruisers were tied to widely separated border worlds, they were often sacrificed attempting to hold back often overwhelmingly superior invading forces. After their lone defending ships were destroyed, borders worlds might be subjected to orbital bombardment or troop landings. When heavier cruisers finally arrived from rear areas to drive out the invaders, they often found devastated colonies and hundreds of dead Federation citizens. Although this policy was effective, in the sense of having prevented any long-term occupation or permanent loss of Federation territory, critics charged that it actually invited attacks by making Starfleet defenses static and predictable. As threat vessels became faster, they were often able to attack and destroy defending Starfleet light cruisers long before heavy cruisers could arrive. Critics claimed the policy also did not fully exploit the strength of heavier cruisers, which were kept within Federation controlled space to avoid the expense of operating them on lengthy missions beyond Federation borders.

A new Command Directive issued in May 2250 made official a policy that had been evolving over the previous five years. Because the powerful new Constitution and Pyotr Velikiy heavy cruisers were extremely well armed and could quickly penetrate free or enemy-controlled space, they had come to represent the Federation's first line of defense. Rather than waiting for hostile forces to attack, the heavy cruisers were to venture forth and prevent potential threats from developing or to extinguish them before they could endanger the Federation. This proactive, or forward-leaning, defense was not as aggressive as a preemptive strike policy but instead worked with Federation diplomacy to deny potential hostile forces access to areas from which they could easily attack heavily populated areas of the Federation. To fully realize this policy, large numbers of small, fast ships would be needed to protect and hold areas of space pioneered by heavy cruisers and to support Federation diplomatic efforts.

Two New Destroyers Are Ordered

To support Federation diplomacy, the new proactive defense policy, and defensive actions against the Klingon Empire, the Starfleet Office of Strategic Planning suggested the construction of large numbers of small cruisers or destroyers. The new ships were to be extremely fast, well-armed, stealthy, and inexpensive to construct and operate. Two classes were envisioned: longer-range, powerfully armed, twin-nacelle ships called Avengers, and shorter-range, less powerfully armed, single-nacelle ships called Predators. One hundred ships of each class were to be constructed at Earth, Mars, and Andor, and at new shipyards to be established throughout the Federation. Several advanced technologies developed for the Constitution and Pyotr Velikiy classes were to be used for the new ships. These included smaller versions of the Pyotr Velikiy's main sensor/deflector with its characteristic long resonance tunnel; a high-absorbance shield system; compact, rapid-fire photon-torpedo tubes; and a powerful impulse drive.

Before starting work on the Avenger and Predator destroyer classes, Starfleet had developed a similar ship based on Constitution. The Hermes-class scout (NCC-S585), which entered service in 2246, used a Constitution primary hull only slightly decreased in diameter and thickness and a full-size connecting dorsal attached to a single Sabre nacelle. Because of the thin connecting dorsal Hermes was forced to accept a small reactor and few antimatter storage bottles, but still weighed nearly 110,000 t. Performance and capability were predictably poor. Most Starfleet crews unlucky enough to serve upon Hermes-class ships described them as resembling "poorly altered suits." Although only 17 Hermes scouts were constructed, a similar layout was used for the Predator-class destroyer.

Design work on Avenger and Predator began at Utopia Planitia, Mars, in the fall of 2250. Despite objections from Andorian engineers, both ships had the conventional layout of a disc-shaped command hull attached by a neck to the warp drive system. Although the boomerang-shaped, Andorian-designed Kestrel-class ships, which had entered service in 2223, were rugged, hard-hitting destroyers well liked by crews and by Starfleet Command, the more common layout had since become the de facto standard for Federation starships. While flat, single-hull Andorian layouts did have the advantages of higher speeds and smaller lateral and frontal profiles, most ship's systems were now designed for the standard layout and often required significant alterations for installation in Andorian-designed ships. Furthermore, crews seemed to prefer serving on ships with more conventional layouts. In particular, the large, circular outer corridors of primary hulls (which was more than 300 m long in Constitution and Pyotr Velikiy), were popular late-night running tracks for off-duty personnel.

The warp power plants for the new ships were the SSWR-XVIII-A (Avenger) and SSWR-XVIII-B (Predator) M/AM reactors, which were scaled down versions of the SSWR-XV developed for Constitution. Although the SSWR-XV was the main reason Constitution had been delivered 3 years late, the SSWR-XVIII reactors had progressed smoothly through development and had been waiting for a suitable hull since 2247. Weighing less than 200 t, the new reactors were compact but more powerful than the reactors in the much larger Valley Forge class of 2227. By any measure, Avenger and Predator would be extremely powerful ships for their size.

The command (or primary) hulls of Avenger and Predator were nearly identical. In both classes the circular, 77-m-diameter command hulls held command centers, the duotronic logic core, crew quarters, life support machinery, and cargo holds. The hull's dorsal promontory (mound) was concentric with the underlying main disc but had an unusual frontal extension that housed the twin photon torpedo tubes. The bridge module was similar to the uppermost part of the bridge complex of the Constitution and Pyotr Velikiy classes but was slightly submerged and slightly forward of the hull's center. Flanking the bridge were two longitudinal emitters for the "Bulwark" shield system, placed externally because of the small size of the hull. Another concession to size was the tunnel-like 42-m-long shuttlecraft bay, which was placed sternward of the dorsal hull promontory and rested for half its length upon the connecting dorsal. Embedded in the rim of the main hull disc was an emission suppression system designed to increase the ship's stealthiness. The main navigational deflector was adapted from that of Pyotr Velikiy. Mounted below the ventral primary hull, the deflector had a dynamic, small-diameter emitter/receptor antennas with a long resonance tunnel extending far sternward.

Attached to the rear of the primary hull was a thick, deep connecting dorsal. In Avenger, the neck held the powerful impulse deck with its associated thrust emitters, reactors, and deuterium tanks. Beneath the neck was the small (50-m-long) engineering hull containing the SSWR-XVIII-A reactor, and antimatter storage bottles. The twin 97-m-long Bulldog warp nacelles were attached to either side of the engineering hull by 45-m-long "cranked" nacelle supports. In the front of the engineering hull was an advanced shield-cracking, long-range phaser cannon powered directly by the M/AM reactor. In Predator, the connecting dorsal was occupied mainly by engineering spaces for the impulse deck, the smaller SSWR-XVIII-B reactor, and fuel stores and was attached through a small adapter bulge directly to the single centerline Bulldog warp nacelle. These limitations upon auxiliary crew-support facilities and the warp drive system decreased the range and maximum warp speed of Predator but improved performance at impulse because of the significantly lower weight.

Because of the large numbers of ships ordered, construction of the Avenger and Predator classes was divided among six Starfleet shipyards throughout the Federation (San Francisco, Utopia Planitia, Andor, Beta Antares, Prek 2, and Rigel V). Despite the dispersion of production, all ships were built to the same exacting standards with important subsystems manufactured at Mars and shipped on Pachyderm-class cargo ships, and assembled at each yard. Larger structural components, including hull plating and strength members, were manufactured locally. Quality control was maintained by powerful yard bosses, answerable only to the Chief of Starfleet's Construction Bureau. The six yards also competed to construct ships most quickly or with the fewest flaws. The record was held by Andor's Starfleet Yard 4 (Construction Facility Shesshik 7), which assembled and launched USS Drummer (NCC-D124) in 22 days.

The New Destroyers Enter Service

USS Predator (NCC-D200) entered service with Starfleet in the spring of 2252, with USS Avenger (NCC-D100) following in the fall of the same year. Both classes immediately found use in a wide range of roles. First, they were used for intra- and extra-Federation policing duties, such as preventing smuggling and interstellar trade in hazardous and forbidden commodities, enforcing trade agreements and safety regulations, stopping illegal mining (by Federation members and alien powers), protecting merchant shipping, and hunting pirates. Such actions freed larger ships, such as those of the Valley Forge, Constitution, and Pyotr Velikiy classes, to undertake more hazardous missions outside Federation space. A second role was Federation defense. Normal defensive duties included scanning border areas for intruders, mapping and probing the frontier for dangers points and weaknesses, and tracking movements of alien warships and transports in free space and Federation territory. The third role for the new destroyers, the one for which they had been constructed, was the support of colonial, diplomatic, and military efforts to enlarge the Federation's sphere of influence, particularly at the expense of the Klingon Empire.

Although the new destroyers were occasionally based at the borders of Federation territory, much as Kestrels had been, they were more often sent into areas of space newly pioneered by Constitution and Pyotr Velikiy cruisers further beyond the frontier. As the new heavy cruisers drove into previously unexploited territory, Avengers and Predators would lead and escort survey vessels, science ships, habitation assessment teams, terraformers and, finally, mining and refinery ships and colonial transports to tame and settle new solar systems. As had happened in the late 22nd and early 23rd centuries, Federation colonies were occasionally established in areas claimed or controlled by other powers. In such cases, the apparent operating policy of the Federation Colonization Authority was that the presence of Federation settlements and industry turned any area into Federation-controlled territory, deserving as any core system of protection by Starfleet. In such cases, Avengers and Predators would remain on station at these contested colonies, guarding against possible attack. However, the Federation preferred not to expend its valuable ship resources in this way. Territorial claims by powers not openly hostile to the Federation could often be settled by trade agreements, such as import and export quotas; payments of fees; joint-use agreements; mutual defense treaties; or technology transfers. Unlike the young "Imperial Federation" of a half century earlier, the mid-23rd century Federation did not colonize for the sake of expansion. Instead, they expanded to bring more space under control of the Federation and its allies so that the Klingon Empire or other hostile powers could not make use of it.

Because of their large numbers and small size, Avenger and Predator destroyers were extremely active in missions to support Federation diplomatic efforts to contain the Klingon Empire. When the 44 Valley Forge-class ships were the Federation's chief long-range cruisers in the early 23rd century, systems on good terms with the Federation but off the major spacelanes might be visited by Starfleet ships once every few years. However, the 200 new destroyers, which were much faster than the quarter-century-old Valley Forges, could make quarterly or monthly visits to most systems, showing Federation interest, concern, and support on a nearly continuous basis. Of course, some systems resented what they considered Federation intrusion into their affairs or felt they had been become virtual colonies of the Federation, but most powers living in the shadow of the Klingon Empire felt reassured by the numerous port calls. With the lure of Starfleet protection, they were more willing to conclude trade, cultural, and technology agreements with the Federation. The visiting Starfleet vessels also assisted Federation and allied commercial operations, commodity transport, and communications; provided timely intelligence and diplomatic information to Federation officials; and couriered high-priority personnel and materiel throughout Federation-controlled space. Most importantly, the new destroyers ranged widely throughout free space bordering the Klingon Empire, bringing much of it safely under Federation control or, at the very least, solidly into the Federation's sphere of influence.

Working with the Federation Diplomatic Corps, the new destroyers helped to establish and maintain peace between minor powers, which were then made part of the Federation's informal coalition against the Klingons. For example, in Sector 212 the Tomta had been at war with the Urjo in a neighboring star system for nearly three centuries. Apparently, each race had believed it was the only sentient race in the galaxy and reacted violently when it learned otherwise. The fact that the two races were nearly identical genetically, both having been created by an ancient humanoid race, increased rather than lessened their hatred for one another. Because the systems were only 3 ly apart, the Tomta and Urjo, although limited to sublight speeds, were able to prosecute a slow-motion projectile war with atomic-tipped missiles and accelerated asteroids. However, the Urjo's breaching of the lightspeed barrier in 2255 promised to escalate the hostilities to a much more violent level. With the rationalization that any interstellar conflict was a threat to galactic peace and security, the Federation declared their right to intervene. In June 2255 the Avenger-class ships USS Rover (NCC-D164) and USS Volunteer (NCC-D194) entered orbit around the Tomta and Urjo homeworlds and requested that peace talks be started. Both governments refused to negotiate, so their leaders were beamed aboard the destroyers for "consultations" with Federation diplomats. After 2 months as guests of Starfleet aboard the Belleau Wood-class command ship USS Brandywine (NCC-1559), the leaders of Tomta and Urjo signed a mutual treaty of brotherhood and instruments of friendship with the Federation. In exchange, the Federation offered a wide range of technical, agricultural, and military assistance, access to the Federation's commercial and banking systems (including convertibility of domestic currency with Federation credits), and frequent visits from Starfleet. (The Tomta and Urjo subsequently formed an official union, then joined the Federation in 2291.) With the Federation's urging, both government extended their territorial limits to 5 ly and limited access to Klingon ships. This action was effective in forming a barrier to Klingon free passage across Sector 212 and preventing Klingon illegal mining in neighboring systems. Through similar actions with many other independent systems, the Federation was able to restrict Klingon movements in large areas of previously free space.

Before 2256 most military actions undertaken by Avengers and Predators against the Klingon Empire had been defensive, or at least nonoffensive, in nature. Launched from border worlds, starbases, or destroyer tenders, the new destroyers ranged in large numbers across free space and, occasionally, Klingon treaty territory, to monitor subspace communications, starship movements, starbase ship traffic, shipyard construction, mining operations, and shipments to and from colony worlds. Some observations were made directly by the destroyers, while other were made remotely by highly stealthed, autonomous sentry devices released by destroyers in free space or within Klingon territory. Because of the relatively peaceful relations between the Federation and the Klingon Empire, Avengers and Predators operated under strict rules of engagement. When challenged by Klingon warships, most often short-range D6 cruisers, the Federation ships were ordered to refuse combat unless absolutely necessary to avoid capture or destruction. However, since they were twice as fast as the short-range D6s, Avengers and Predators could usually return to base with little more than some light hull scorching and interesting tales to tell at the canteen.

Changes in the Klingon Empire

The easing of tensions and increased contact between the Federation and the Klingon Empire had profound effects on both powers. The arrival of Klingon ambassadors and their staff in Paris and other Federation capitals sparked a great deal of curiosity. The Klingons were generally believed to be a barbaric, almost animal race that feasted on raw, still-living flesh. Therefore, the appearance of Klingon ambassadors in their exotic finery of fur, horn, and scales did not disappoint. A fad for Klingon-inspired fashions quickly swept through the Federation, as did fads for Klingon art works, opera, martial arts, language courses, and food (although good gagh was quite hard to find, even in New York City). Socially ambitious Federation citizens vied to have Klingons attend their private parties and public functions. Federation citizens began to believe that the Klingons were not so different from them after all. These beliefs led to hopes for a "Klingon Spring," in which the winds of democracy and liberalism would blow through the Empire and transform it into something resembling the Federation.

The Treaty of Korvat allowed independent foreigners to enter the Klingon Empire for the first time. Previously, most Klingon contacts with other cultures had come in the form of military conquest or intimidation of less technologically advanced races, from whom the Klingons wanted only mineral resources, obedience, or slave labor. Now, however, the Klingon Empire was slowly opening itself to limited commercial and cultural relations with the Federation and the rest of galaxy. Liberal elements within Klingon society welcomed the chance to experience the full spectrum of galactic culture, scholarship, and philosophy. The Islamic Quran, the Christian Bible, the Neo-Uurist Celestial Commentaries, and other religious works were translated into Klingonese, as were literary, political, and philosophical works from such authors as Earth's Sun Tzu and Niccolo Machiavelli, Vulcan's Surak, and Andor's Thevis VII. Supporters of Klingon openness believed the Empire would emerge stronger through selective exposure to external ways. In particular, Federation manufacturing, economic, legal, and agricultural practices could greatly increase the efficiency of Klingon industry, food production, and society in general, elevate standards of living, and make the Klingon Empire better able to challenge the Federation in the future. While most Klingons did not embrace foreign influences whole-heartedly, they were sufficiently pragmatic to understand that the Empire could benefit by learning from the Federation and other galactic powers. Indeed, the Klingons had no misgivings about making use of technologies developed by alien races they had conquered. The great difference now was that the Klingons had less control over the influences to which the Empire was exposed and, as a result, felt more threatened by them.

A sizable minority of Klingons viewed all foreign influences with contempt. These traditionalists believed that anything that diluted the "precious spiritual integrity" of the "Klingon body" would lead to the eventual downfall of the Empire. Held in particular disdain were those who proselytized for major Federation religions in an attempt to bring a more peaceful spirituality to the Klingon Empire. However, one reason that these foreign beliefs were able to establish themselves in the Empire was that the Klingons had been a largely secular people for the last several hundred years since the overthrow of the last emperor and the "deaths" of native gods. Instead of adhering to traditional Klingon forms of religion, which included the cult of Kahless, rigid notions of honor, and ancestor worship, most Klingons of the mid 23rd century valued clan ties, social advancement, and success in combat. In such an environment, many foreign religions, or at least some aspects of them, attained surprisingly widespread popularity, especially in areas of the Klingon Empire bordering the Federation. In fact, the Roman Catholic church appointed Kej'rik of the House of Kej'tar as Bishop of Qo'noS in 2256.

More widespread were political differences over the future direction of the Klingon Empire. After assuming the chancellorship in 2244 and signing the Treaty of Korvat in 2249, K'tok had been making enemies among members of several powerful Great Houses, particularly the houses of Nurragh, Temosh, Maach, and Cho'kwok. Although K'tok had shown his bravery and aggressiveness in attacks against the Federation during the late 2230s and early 2240s, he was now branded as being weak, foolish, traitorous, and even feeble-minded rather than pragmatic for having agreed to limits, albeit temporary, upon Klingon military actions and territorial ambitions. That a treaty had been signed with an "effete," "degenerate," and "mongrel" power such as the Federation compounded his perceived errors. These opposition Houses were even more incensed by the actions the Empire was forced to undertake in the realms of diplomacy and trade. K'tok's opponents felt that such actions humiliated the Empire, by forcing it to treat non-Klingons as equals rather than conquering them and ravaging their worlds. That these demeaning diplomatic trade activities had not secured the much needed raw materials for the Klingon war machine added injury to these insults. In 2255, Kurox, leader of the House of Nurragh, took the floor of the Great Hall on Qo'noS and accused K'tok of foolishly exposing the Empire to the corrupting influences of the Federation, which disrespected the Klingon people and desired their annihilation. By redeploying ships from the border to diplomatic duties throughout the galaxy, K'tok was said to have signaled the submission of the Empire to Federation predation and domination. Indeed, claimed Kurox, swarms of Federation destroyers were operating with abandon throughout space that rightfully belonged to the Klingon Empire. According to Kurox, military preparedness had seriously deteriorated, leaving the Empire prostrate and defenseless against an all but inevitable invasion by the hated Starfleet.

Although Chancellor K'tok was certainly not the liberal architect of a "Klingon Spring" hoped for in the Federation, he saw no great harm in allowing selected external influences to strengthen the Empire. Indeed, both K'tok and his opponents sought the continued strength and expansion of the Klingon Empire but differed only in the pace and methods to achieve that aim. That concerns about foreign influences upon the Klingon Empire were seized upon by Chancellor K'tok's political opponents to bolster their plans for a return to power was ironic and hypocritical, since most of these men were pragmatic, secular Klingons who had themselves enjoyed and benefitted from contacts with the rest of the galaxy. Many were, in fact, devotees of the Human playwright Shakespeare, who they felt provided valuable lessons in the pitfalls of command. Several years earlier, the opposition House of Cho'kwok had even sponsored a tour by the Karidian Players, a famed Shakespearean repertory company from the Federation, and supported the first performances of Shakespeare plays translated into Klingon. Although they had previously shown little interest in traditional Klingon spirituality, K'tok's opponents saw Klingon religious fundamentalism as an immense source of energy to power their political ambitions. Accordingly, Kurox charged in the Great Hall that all foreign influences were anathema to the true warrior spirit of the Klingon people and declared that he and his allies would henceforth adhere strictly to traditional Klingon values and purge themselves mercilessly of all "foreign corruption." The houses of Nurragh, Temosh, Maach, and Cho'kwok announced that priests from Boreth would serve as their advisors on all matters both secular and spiritual. Most of all, Kurox said, the Klingons needed a strong, decisive leader to lead them through these uncertain times.

To be sure, this atavistic vision for Klingon society was born more of political opportunism than spiritual conviction. Nevertheless, these attitudes were seen by many as an antidote for the Klingons' present sense of malaise engendered by their recent military and foreign-policy failures. These attitudes gradually permeated Klingon society over the next few decades despite opposition from more liberal elements. These values ushered in a new type of Klingon society, one in which rigid notions of public honor were adhered to at the expense of all other considerations. Blood ancestry and social caste were elevated to extreme importance, and ancestors and relics were worshipped to a fetishistic degree. The complexity, nuance, and cunning of Klingon military and political society were replaced with blind, unquestioning loyalty; solemn, torch-lit rituals of pain and blood; drunken, brawling camaraderie; and turgid fantasies of death in glorious combat against impossible odds. These new rules and attitudes of society initially provided a comforting veneer of order and purpose for those Klingons confused and fearful in a period of strange new influences and great change. However, by rewarding ancestry, appearance, and obedience rather than intelligence and skill, these same rules and attitudes were eventually to prove tragically wasteful and destructive when the Empire needed to adapt quickly to even more dire challenges and apocalyptic threats over the next century.

The Death of K'tok and Civil War

In October 2256 Chancellor K'tok died in his sleep at the relatively young age of 87 years. As his death fulfilled a traditional Klingon's warrior curse against the cowardly, K'tok was likely assassinated by his political foes who believed he had not taken a sufficiently aggressive stand against the Federation. Even before K'tok's death had been revealed, planetary holdings of his House of Chorr and the allied House of Gu'dek were attacked by military units of the powerful Houses of Nurragh, Temosh, and Maach. In ferocious fighting that lasted more than 2 months, scores of ships were destroyed and perhaps tens of thousands of soldiers and civilians were killed, although the exact figures are unknown. However, several planets were effectively sterilized by orbital bombardment with antimatter munitions and the nerve agent theragen. After the remnants of the old chancellorship had been swept away, the victorious opposition forces moved to occupy Qo'noS, the imperial seat. Kurox of the House of Nurragh, K'tok's most vocal critic, was immediately named the new chancellor in a unanimous decision of the High Council.

Kurox's first act as chancellor in January 2257 was to withdraw from the Treaty of Korvat, thereby laying claim to all areas under dispute and refusing to recognize the legitimacy of the Treaty-defined borders of the Federation. Kurox repeated his belief that the Federation was determined to destroy or emasculate the Klingon Empire and declared that henceforth the Klingon Empire would not cooperate in its own destruction by having any diplomatic dealings with the Federation. He then ejected all Federation citizens, including embassy staff, from the Klingon Empire, branding them all Federation spies. All Klingon ambassadors were recalled, and the border with the Federation was closed.

To deal with incursions by Starfleet destroyers in what he considered Klingon territory, Kurox withdrew most ships from their diplomatic duties and reassigned them to areas bordering the Federation. However, because of the large number of ships destroyed in the recent fighting and the technical superiority of Starfleet's new destroyers, Federation activity in the disputed areas was not significantly restrained. New ships and new tactics would be needed.

The Federation Reaction

The Klingon withdrawal from the Treaty of Korvat was not completely unexpected by the Federation. The Federation had received information from its operatives in the Klingon Empire about the growing anger over the perceived failures of K'tok's rule and had witnessed firsthand (and, indeed, had contributed to) recent Klingon failures in diplomacy and trade. Starfleet had monitored military communications and fleet movements indicating impending attacks on K'tok's chancellorship. Starfleet had even strengthened its border defenses in case the subsequent fighting threatened to spill over into space controlled by the Federation or its allies. In fact, K'tok's overthrow and the Klingons' withdrawal from the treaty were generally seen as a long-expected "correction" of a highly anomalous Klingon regime and a return to the status quo during most of the period since first contact with the Klingon Empire. However, the Federation decided to make as much political capital as it could from the Klingon treaty withdrawal, with Federation President Klest calling it "a treacherous act that pushed the galaxy to the brink of interspace war."

Even before the Klingon withdrawal from the treaty, the Federation had discarded its initial fascination with Klingon exoticism and begun to pay greater attention to disturbing reports about Klingon colonial policies, which included environmental devastation, slave labor camps, the killing of hostages, and genocide. The Federation had also learned that Klingon relations with independent planets often involved first contacts with nonspacefaring civilizations; offers of inappropriately advanced weaponry and spaceflight technology; and offensive assistance in local, global, interplanetary, and interstellar conflicts. Although such practices had long been rumored, closer contact with the Klingons lent greater credence to Federation suspicions. Starfleet Intelligence also came to suspect that the Klingons had used the increased access to Federation space afforded by the Treaty to undermine Federation security. The Klingons were believed to have established an extensive espionage network within the Federation; even more alarmingly, intercepted Klingon communications suggested that Klingons agents posing as members of Federation races had successfully infiltrated Starfleet and the Federation bureaucracy.

Despite the violent political upheavals in the Klingon Empire and its dire shortage of raw materials, Starfleet and the Federation diplomatic corps still viewed the Klingon Empire as a monolithic, monoracial dictatorship bent on galactic conquest. Some analysts even feared that "momentum" or "war fever" from the recent fighting in the Empire would somehow lead to immediate large-scale attacks upon the Federation. While such attacks did not materialize, the Klingons were believed certain to confront the Federation again, although when and how was still a subject of debate. Because of severe ship losses during the recent civil war, the best guess was that the Klingons would be unable to mount a serious challenge to the Federation for at least two decades, unless they were able to secure a more reliable source of raw materials. However, the Klingons were unlikely to withdraw behind the previous treaty border, as the Romulans had done, but instead would renew their attacks upon Federation outposts and more aggressively defend their declared territory.

The Resource-Denial Campaign Escalates

The Federation saw the Klingons' withdrawal from the Treaty of Korvat and their expected post-civil war retrenchment as opportunities to escalate their campaign of resource denial. First, the Klingons' apparent rejection of peaceful means of resource procurement gave the Federation an excuse to resort to its own nonpeaceful means to further restrict Klingon access to resources. Second, the Federation hoped that the Klingons' unilateral withdrawal from a legal and valid treaty would prove to non-Federation governments that the Klingons could not be trusted. Third, the Klingons' ship losses during the civil war made them less able to resist Starfleet actions or carry out offensive operations of their own. Furthermore, if the Klingons attempted to match Federation ship production, they would be entering a ruinous competition they could not win.

One component of the Federation's escalation of its resource-denial campaign was diplomatic. Although the Klingons had been able to obtain small quantities of raw materials through trade, the Federation now sought to completely shut off such imports to the Klingon Empire. By educating the Klingons' non-Federation trading partners about the "true" nature of Klingon diplomatic and military activities, the Federation hoped to persuade them 1) to sign exclusive trade agreements with the Federation or at least to agree not to deal with the Klingons; 2) to deny refueling, transit, shore leave, and communications-relay privileges to Klingon ships across their space; and 3) to expand their sovereign territories to a radius of 5 ly from their suns, thereby decreasing the amount of free space open to the Klingons. The education of neutral governments to the Federation's point of view involved showing them intercepts of Klingon subspace communications, covertly obtained documents, recordings of diplomatic discussions, and visual evidence of Klingon atrocities. Most of this information was genuine, but the Federation was not above enhancing or manufacturing evidence when necessary.

To compensate these governments for potential trade losses, the Federation was willing to purchase enormous quantities of raw materials at prices much higher than the Klingons were able to pay. The Federation could arrange payment in any number of ways, including the freely convertible Federation credit. Although the Federation preferred to use such carrots to persuade governments not to deal with the Klingons, it was not above using the occasional stick, such as downgrading diplomatic relations, imposing extremely high tariffs and trade embargoes, and withdrawing transit privileges. Of course, if a neutral government claimed it was too afraid that the Klingons would retaliate if it stopped dealing with them, the Federation would place it under the friendly umbrella of Starfleet protection. Where the Klingons had traded commercial privileges for military assistance or intervention in an ongoing conflict, the Federation sent teams of diplomats and Starfleet officers to settle disputes and make military power superfluous. Most warring governments could be persuaded to lay down their arms in exchange for Federation guarantees of peace, security, and prosperity.

New Destroyers Unleashed

The second component of the escalated resource-denial campaign was military. Unlike the earlier phase of the campaign, which had involved only defensive, surveillance, and reconnaissance activities, the post-treaty campaign involved more aggressive, even warlike, activities designed to prevent the Klingons from both obtaining mineral resources and benefitting from resources already in their possession. Most of these activities were carried out in Klingon-controlled space by Avenger and Predator destroyers. Some aspects of this military campaign can be illustrated through the actions of James T. Kirk, who before his legendary missions aboard the Constitution-class USS Enterprise (NCC-1701), was a daring and creative destroyer captain.

While at Starfleet Academy Kirk was studious and serious but occasionally showed signs of brilliance, as when he reprogrammed a simulator to allow a solution to the Kobayashi Maru exercise. However, his early years as a junior officer were uneventful and suggested, at best, a gradual rise through the ranks along with other members of his cadet class. All that changed in 2257 when Captain Garrovick, the senior officers, and half the crew of USS Farragut (Constitution class, NCC-1711) were killed in an attack by a gaseous lifeform at Tyco IV. Kirk quickly assumed command and piloted Farragut to safety at Starbase 5. Although Kirk blamed himself for the deaths, his decisive actions had attracted the attention of Starfleet Command, which began grooming him for early command of his own starship. While recuperating from injuries sustained aboard Farragut, Kirk spent 6 months at Starfleet's Advanced Tactical School on Izar. Kirk next served for 9 months as executive officer aboard the heavy cruiser USS Tav (Pyotr Velikiy class, NCC-1674) under Captain Matthew Decker. To develop his nonmilitary skills, Kirk was then sent in succession to Starfleet Intelligence in Washington, the Judge Advocate General's Office at Gravenhage (the Hague), the Federation Foreign Service Institute on Vulcan, and the Starfleet Language Academy on Cait.

In February 2260, Kirk was given the command of USS Interceptor (NCC-D243) a Predator-class destroyer assigned to Starfleet Destroyer Squadron 5 (DESRON 5) operating from the destroyer tender USS Siberia (Pachyderm class, NCC-DT22) just outside the Klingon border at Parchuk IX. Although Kirk, at age 27, was the youngest combat-ship captain in Starfleet by several years, he quickly gained the confidence of his crew through his intelligence, decisive command, and daring. For the first few months of his command, USS Interceptor served as the "wingman" of USS Snapper (NCC-D278) under the more-experienced Captain José Dominquez. Interceptor usually stood by to scan for enemy ships and protect Snapper as she went about her more dangerous work.

One mission of Federation destroyers was to maintain an extremely close watch on Klingon ships, both warships and transports, wherever they ranged in supposedly free space. Starfleet intended to clearly indicate to the Klingons that their vessels were not welcome in areas the Federation considered under their control. This shadowing led to several incidents in which Federation and Klingon ships were damaged in collisions with one another. Starfleet destroyers also boarded numerous Klingon cargo ships, passing through free space or within the newly expanded 5-ly territorial limits of the Federation, to conduct lengthy inspections on the grounds of safety or commercial regulations, transport of contraband, and even pursuit of fugitives from Federation law. Klingon ships were usually found to be in violation of obscure, rarely-enforced regulations, such as not keeping records of lifeboat drills, not possessing cargo manifests in Federation-standard English, and unsanitary food preparation areas. The ships were then towed to the nearest starbase and impounded pending payment of hefty fines or forfeiture of their cargoes. Klingon warships were, however, treated much more harshly; if they entered the 5-ly Federation exclusion zone or the territory of a Federation ally, they were immediately fired upon without prior warning.

Destroyer operations during this period have been portrayed in the popular media as "run and gun" operations in which destroyers, according to one best-selling holonovel of the time (Lone Star Ranger by Justice McMillan, Mazeppa Publishing, Rigel V, 2259), "smashed the Klingons in their ridged noses and warped home with a flock of angry Birds of Prey (sic) in hot pursuit." Such popular accounts wrongly suggest that Starfleet destroyer operations were intended to provoke Klingon responses. In fact, destroyers aimed to carry out their missions with extreme stealth and to have safely returned to Federation space before their destructive actions had occurred, much less been detected. The ideal covert operation was one that the Klingons did not realize had been carried out.

In May 2260, Interceptor was "promoted" to the lead ship of a two-ship team with USS Grenadier (NCC-D236). Kirk, often called "The Boy Wonder" because of his youth, was particularly adept at operating in hostile territory without being detected. First, he was skilled at using the interstellar terrain to travel in areas that decreased the risk of sensor contact. He would maneuver his ship through nebulae, subspace lacunae, and solar storms and hide behind asteroids and comets until he passed beyond the scanning range of hostile bases or ships. Second, he used these same hostile ships to mask his own ship's emissions. For example, he often followed in another ship's subspace wake or shadowed at a fixed distance so that his ship's sensor contact would be misinterpreted as a sensor reflection. Third, Kirk worked with his tactical officers and engineers to re-tune the resonance frequency of his warp coils to mimic those of Klingons warships and transports. Finally, Kirk also spoke fairly good Klingonese, which he used to talk his ship out of trouble on more than one occasion. (However, rumors that Kirk once talked a Klingon computer "to death" are probably untrue.)

As a rule, destroyer crews, who served in small numbers upon very fast ships, considered themselves a dashing elite. Befitting their swashbuckling image, destroyer captains were given considerable autonomy to plan and carry out missions in transborder areas. As Kirk grew more bold, he often took his ships a full sector, as much as 20 ly, past the treaty border on missions lasting several weeks. In one particularly audacious mission, he used Interceptor's speed and stealth to evade Klingon defenders near Therik G, then entered the Mosa nebula, where he waited for 3 days for a Klingon automated transport to pass by. He hid beneath this transport for 4 days, then destroyed it as it approached ak-Jom'mak shipyards at Sima IV. He tuned Interceptor's warp coil emissions to mimic those of the destroyed transport, then approached to within 200,000 km to release mines and monitoring devices that entered the shipyard and attached themselves to ships, drydocks, and maintenance vessels. After running at high speed for 4 days, Interceptor hunted targets of opportunity near the Epsilon Lalza system, destroying communications arrays, sensor stations, and M/AM refuelling depots. He next travelled within the subspace wake of a Klingon D6 cruiser for 12 days at wf 5 to take ultrashort-range sensor readings of the large fleet base at Kurrdanj II, then returned to Federation space by shadowing a D7 cruiser as it headed out for a patrol in the former TBZ.

A favorite target of destroyers on resource-denial patrol was Klingon cargo trains. Non-time-sensitive raw materials, such as unrefined mineral ores, that were extracted from a single location at a steady rate over many years were most economically transported via autonomous cargo ships. These ships were immense, often comprising a warp-drive-equipped robot tractor towing up to five cargo modules with a total length of 1,000 m. Because of their enormous displacement, often several million tons, these cargo trains were extremely slow, usually slightly more or less than wf 3, and might need 5 years to reach processing stations from mining regions in the antispinward sectors of the Klingon Empire. However, their low speeds, nonexistent or minimal crews, and high economic value made them fat, easy targets for marauding destroyers. The Klingons occasionally attempted to protect the cargo trains with escort cruisers, but the duty was extremely arduous and tedious, and was only occasionally effective for preventing direct attack by destroyers. If a cargo ship were attacked, the Klingon escort most often made a token, face-saving attack against the Federation destroyer, then was allowed to escape destruction. Once left undefended, the cargo train was usually destroyed or, if the cargo was extremely valuable, the train was divided and diverted to Federation space. The main means of destroying cargo vessels, however, were mines, against which escorts could usually provide no defense. Federation mines were extremely sophisticated. They ranged in size from 10 cm to 2 m in diameter with warheads of varying size. Most mines relied on passive sensors and could be programmed to detonate only when sensor contact of a certain type had been made. Because the programming could be changed remotely by subspace commands, mines could be instructed to detonate upon sensor contact with differing targets as the need arose. Mines, depending on their size and fuel load, also had limited potential for independent movement, so could reposition themselves in streams of higher ship traffic to increase the likelihood of contact and home in on targets to prevent escape. Finally, mines could be instructed to self-destruct when they were no longer needed.

From 2256 to 2265 Federation destroyers laid countless thousands of mines: in geosynchronous orbit around Klingon planets; at the entrances and exits of starbases, shipyards, refueling depots, and fleet assembly areas; along the most heavily travelled space lanes throughout the spinward sectors of the Klingon Empire, and across potential invasion routes into the Federation. Although only a small percentage of mines ever detonated against an intended target, their mere presence required avoidance and eradication measures for the safety of Klingon military and commercial ship traffic. These measures included lower ship speeds to give more time to detect and avoid mines and the construction of mine sweepers and mine hunters, which were small, autonomous robots that emitted the sensor and subspace signatures of a target ships to attract and detonate mines. All these countermeasures were extremely costly in terms of Klingon time and materiel and generally complicated all ship traffic, results that made mine warfare extremely attractive to the Federation.

The Klingon Empire Strikes Back

Although the Klingons' withdrawal from the Treaty of Korvat had been intended to help extend their control over the disputed territories, it seemed to have the opposite effect. Starfleet destroyers continued their surveillance and reconnaissance activities in the former TBZ and by the early 2260s freely carried out missions of harassment and sabotage deeply into what had previously been treaty-defined Klingon territory. The Klingons were, of course, outraged by these incursions, but debated over how they should respond. Some Great Houses demanded that the Klingons launch an immediate punitive war against the Federation, both for their current "disrespectful" violations of Klingon space and for the previous humiliating attempt to turn them into a nation of shopkeepers. Other Houses counseled that the Klingons should maintain pressure upon the Federation while slowly rebuilding their forces for a future war. Instead of worrying how to "punish" the Federation, Chancellor Kurox's immediate problem was how to stop the incursions. However, he found to his great frustration that his options were greatly limited by shortages of ships, raw materials, and the political fissures that threatened to tear the empire apart. After seizing power, Kurox began to understand the challenges that the deposed K'tok had faced but vowed not to make the same mistakes. Far from being the monolith so feared by the Federation, the Klingon Empire was held together only by a common origin, a reviving form of religious nationalism, and the threats from powerful and aggressive enemies. However, because almost every action he took was likely considered too weak by the most aggressive Houses of the Empire (including his own), he risked suffering the same fate as K'tok.

Kurox's attempt to halt the incursions by reassigning D7 heavy cruisers from diplomatic duty to border patrols was only partly successful. These cruisers had been built to project Klingon power and were ill-equipped to hunt down and destroy the fast, agile Predator and Avenger destroyers. The 20-year-old D6 light cruisers, which had been built specifically for rapid cross-border strikes against the Federation and other powers, were more maneuverable, but were not designed for long patrol cruises. However, ship losses from the civil war of 2256 and the need to defend the Empire's border with the Romulans meant that the Klingons could not field adequate numbers of even these less-than-suitable ships. Furthermore, these ships were little help in dealing with the autonomous mines and surveillance devices that plagued the Klingon space lanes. Doing so would have required a level of technological sophistication that the Klingons simply did not possess.

In a move meant in part to placate those in the Empire calling for retribution against the Federation, Kurox responded to the Starfleet incursions by launching selective punitive attacks against Federation border colonies. Unlike the precise Starfleet attacks on Klingon military assets, these Klingon attacks were much less discriminate, often killing scores of Federation civilians as well as Starfleet personnel. These "soft" targets were chosen because civilian worlds were not as well-defended as military targets, making the attacks operationally and technologically less difficult, and because the Klingons believed that the Federation would be unwilling to invite further civilian casualties by continuing its incursions into Klingon space.

The official Federation response to these Klingon attacks was predictable shock and outrage. The Federation news media echoed these sentiments and called for stronger efforts to defend the Federation, including war. However, the Federation Council was well aware that the Klingon attacks were in direct response to Starfleet destroyer operations, the full extent and true nature of which had not been publicly revealed. Because the attacks occurred at randomly chosen single colony worlds and were clearly not intended to seize Federation territory, the Federation Council was forced to accept the likelihood of continued Klingon retaliatory attacks and did its best to prevent them, by increasing the number of ships defending the border areas and by tightening its stranglehold on Klingon resources.

However, many Starfleet officers saw the Klingon attacks as an disproportionate escalation of the cold war that could lead to a hot general war. Captain Ambika Lazarev, commander of DESRON 16, used terminology from the ancient Earth sport of baseball, which was popular among destroyer crews, to express the feelings of most of her fellow officers: "If you bean my clean-up hitter, I can go ahead and drill your number 4 man and it ends there. I don't go after your starting pitcher, much less the batboy or some old lady in the stands." What she meant was that a symmetrical, proportional response by the Klingons upon military or industrial targets was acceptable and expected. What was not acceptable were "terror attacks" on civilian noncombatants.

The Klingons Gain an Ally

What the Federation did not appreciate was that the Klingons were not playing baseball, they were fighting for their lives. By 2262, the shortage of strategic resources within the Klingon Empire had become dire. New ship construction had nearly ground to a halt, and even parts needed to maintain existing ships were in short supply. More and more ships fell into disrepair and were forced to remain in port. Without a stable source of raw materials, the Klingon Empire would be soon be completely defenseless against whatever humiliations the Federation was no doubt already planning and would also be hard pressed to resist attacks by the Romulan Star Empire on its coreward border. Choosing the lesser of two evils, the Klingons entered into negotiations with the Romulans, with whom they had been fighting for almost a century. Armed with new negotiating skills learned from dealing with the Federation and other powers, the Klingons managed to secure raw materials, cloaking technology, mine-sweeping equipment, and advanced sensors and sensor countermeasures from the Romulans in exchange for M/AM reactor technology and one third of the D7 cruisers constructed. The Romulans apparently decided that they hated the Klingons somewhat less than they hated Humans, who had humiliated them a century earlier in the Earth-Romulan War and were now the dominant power in the Federation.

The first D7s built with Romulan raw materials were launched from shipyards along the border with the Romulan Empire in late 2263. Shipyards were established in this area to bring them closer to Romulan sources of raw materials and to escape Federation surveillance. Despite the need for ships to guard against Federation incursions, these newly built cruisers were held secretly in reserve until the Klingon Empire was prepared to attack.

The steady supply of raw materials from the Romulans also allowed the Klingons to introduce a new class of destroyer in early 2263, the E12 class (also known as the Cha'bip class, after a swift Klingon bird), designed specifically to hunt down Avenger and Predator destroyers; a destroyer destroyer, if you will. The E12 used several components from the 20-year-old D6 but had improved Romulan sensors for findings and tracking hostile ships. Although the E12 was also significantly faster and more maneuverable than the long-range D7 cruiser, its maximum speed of wf 8.2 meant that it was no match for the new Starfleet destroyers, which usually escaped without difficulty at wf 9 or better. However, when Klingon destroyers began hunting in packs, they became much more dangerous. For example, in July 2263 USS Provocateur (NCC-D255), under the command of Captain Daljit Pedersen was releasing monitor drones near the Klingon military-mining colony world of Tesme IV when she was detected and pursued by three Klingon E12 destroyers. Accelerating to maximum burst speed, she was driven into a nebula, which the Klingons had seeded with homing gravitic mines. Provovateur was struck and seriously damaged by a mine. As Provovateur was now limited to impulse speeds, Captain Pedersen realized that she was unlikely to reach Federation space before being discovered by the E12s. Pedersen broke radio silence to send a tightly focused distress signal to squadron-mate USS Spiker (NCC-D280), which rendezvoused with Provovateur and evacuated her crew before she was completely consumed by her M/AM self-destruct charges. Over the next 4 years, the Klingons' new ships and tactics were to have considerable success against Starfleet destroyers, especially with their Moab-class long-range warp missiles, built with Romulan assistance.

By the end of 2263, Starfleet had lost 24 destroyers and nearly 1,000 men and officers in actions against the Klingons. In addition, attacks by the Klingons on Federation border worlds had cost a further 2,000 lives. As the Klingons began to resist Starfleet actions more effectively, the Federation Council began to wonder whether the incursions should be decreased or halted entirely. The Council also began to fear that the resource-denial campaign was not having its desired effect, as the Klingons seemed to have secured raw materials from an unknown source. The Orion Syndicate and other criminal organizations were known to be dealing with the Klingons but were unlikely to be meeting all the Klingons' industrial needs. In contrast to this crisis of confidence among the civilian leadership of the Federation, Starfleet Command had no doubts that the resource-denial campaign should be continued, if not escalated. In fact, a significant number of officers believed that the Federation had a historic opportunity to eradicate the Klingon threat once and for all, but this opportunity was quickly fading, as the Klingon Empire appeared to be recovering its strength. These officers privately drew up numerous plans for war against the Klingons, some of which called for the Klingon homeworlds to be invaded and occupied. Simulations bore out their confidence of a quick Federation victory in such a conflict.

Klingon operatives that had infiltrated the Federation bureaucracy learned of these invasion scenarios, which were unofficial and, therefore, were discussed openly outside the usual Starfleet security protocols. The Klingon High Council viewed these plans with alarm, since they were unfamiliar with the intellectual give-and-take common in democratic societies. The Klingons considered the war plans to reflect the true intentions of the Federation because they believed that plans of such magnitude would not be prepared unless expressly ordered by Starfleet Command and the Federation Council. These war plans were also consistent with recent Starfleet actions in the TBZ and antispinward into Klingon-controlled space. Starfleet destroyers, in addition to interdicting shipments of raw materials, were slowly dismantling the Klingon border sentry system and lines of internal communication, monitoring the movements of Klingon warships, mapping routes into Klingon space, and had mined space lanes that the Klingons would use to send reinforcements to border areas. Also, in response to recent Klingon retaliatory attacks, Starfleet had recalled many Constitution-class heavy cruisers to patrol stations adjacent to the Klingon Empire. The Klingons interpreted the war plans and the recent Starfleet actions as preparations for an invasion of the Empire. The Klingons were determined to strike the first blow in any war but would not be prepared to attack the Federation for several more years.

A Starfleet Conspiracy

In 2263 James Kirk was commanding the Avenger-class USS Spangler (NCC-D173) and the 5-ship DESRON 26. During repairs at Starbase 18 Kirk was approached by Didier Mkembe, captain of USS Kite (NCC-1422, Kestrel class) and a friend from Starfleet Academy, and asked to join a group of young starship commanders who felt that the Federation was being too timid in its relations with the Klingon Empire. These officers believed that the advantages of Federation protection and membership should be extended to all races in the galaxy and that Klingon aggression must be stopped once and for all. To this end Mkembe and his co-conspirators planned widespread destroyer attacks on Klingon colonies along the border and deeper within Klingon territory. These attacks were designed to provoke the Klingon Empire to launch large-scale retaliatory attacks Federation civilian targets so that war would be declared by one side or the other. All areas of space now under dispute, as well as broad areas of Klingon-controlled space, would then be seized by the Federation in a short, decisive war. Mkembe maintained that present Starfleet efforts to contain the Klingons were already costing scores of lives each year with little concrete results. Furthermore, as the Klingons had already launched numerous isolated punitive attacks on colony worlds, Mkembe and his co-conspirators were confident the Klingons could be goaded into even more violent action. These officers considered it criminal that their lives and those of civilians were being sacrificed to maintain the status quo. They also cited their oath as Starfleet officers to protect the lives of Federation citizens from attacks by aggressive races, such as the Klingons. True, the resource-denial campaign was having some effect, but would likely drag on for many more years without a decisive conclusion. The attacks Mkembe proposed were likely to cause the deaths of several thousand Klingons, but Mkembe rationalized these deaths as being necessary to spur major Klingon reprisal attacks that would spark a wider war that the Federation would win. The conspirators felt offensive actions were justified by the goal of a more secure Federation and final defeat of the Klingon Empire.

Federation policy had thus far been to push the Klingons to a point just short of that leading to a declaration of war by either side. However, these young officers welcomed war with the Klingons and were prepared to start one themselves. Kirk recognized his duty to uphold the Federation Charter and his oath as a Starfleet officer to obey the orders of the civilian government. Furthermore, the idea of carrying out offensive actions against civilians was abhorrent to him, as it was to most Starfleet officers. Kirk reported the conspiracy to Captain Matthew Decker of USS Constellation (NCC-1710, Constitution class), his former commanding officer aboard USS Tav, who then notified officers he trusted at Starfleet Command. Acting on the information from Kirk and other sources, Starfleet quietly arrested Captain Mkembe and 4 other young starship commanders. However, they refused to implicate any other officers, so the full extent of the conspiracy remained unknown for many years. Rumors persisted, however, that the conspiracy reached the highest levels of Starfleet Command and involved several dozen officers, including several of flag rank. Even 30 years later, conspirators continued to be uncovered; in 2293, Admiral Lemuel Cartwright, after being arrested for his part in the conspiracy to assassinate the Klingon Chancellor and the Federation President in 2293, admitted that he had been a member of the earlier conspiracy when captain of USS Virginia (NCC-1715, Constitution class).

The Four Days' War

In September 2266, Starfleet held its largest war games in more than two decades in the Wolf 359 system. Intending to simulate the attack and defense of a system in an area claimed by the Federation and an unnamed hostile power, the war games drew the participation of 3 flag officers from the Second, Fifth, and Sixth Fleets, 3 Constitution heavy cruisers, 2 Siegfried dreadnoughts, 1 Pyotr Velikiy heavy cruiser, 4 Valley Forge cruisers, 1 Belleau Wood assault transport, and numerous Predator, Avenger, and Kestrel destroyers. Many Federation diplomats called the war games "ill-timed" and "foolishly provocative," but Starfleet Command maintained that the war games had been three years in the planning and were necessary to ensure fleet readiness. When the Klingons received reports of the war games, they became more certain that the Federation intended to invade the Klingon Empire.

Klingon admirals loudly proclaimed in the Great Hall on Qo'noS that if the Federation invaded the Empire, it would be "committing suicide on the walls of Tong Vey." However, the Klingon High Council decided that if war were to come with the Federation, it would start at a place and time of the Klingons' choosing. The Klingon fleet was much stronger than it had been a mere 5 years earlier, thanks to the addition of nearly 200 new ships, mostly D7 heavy cruisers and E12 destroyers. Many of these ships, including the bulk of the new heavy cruisers, had been constructed along the Klingons' border with the Romulans and held there in reserve, meaning that they had never been observed by Starfleet destroyers.

The recent deterioration in relations between the Federation and the Klingon Empire greatly alarmed neutral governments throughout the Alpha and Beta Quadrants. If full-scale war were to break out between these two extremely heavily armed powers, millions might die, especially if neutral powers and allies were drawn into the conflict. In an attempt to prevent war, the governments of Trillius Prime and Ramatis III, which had helped negotiate the Treaty of Korvat almost two decades earlier, urgently requested peace talks. The Federation agreed, maintaining that it had always stood for peace and the rule of law. The Klingon government also agreed to negotiations but insisted, as a gesture of good faith, that all military operations in the former TBZ and across treaty-defined borders be suspended. The Federation, believing in its superior strength, agreed to the moratorium.